Lajme

string(62) "pkk-ends-armed-struggle-seeks-peaceful-path-for-kurdish-rights"English

Gazeta Express

12/05/2025 20:14PKK Ends Armed Struggle, Seeks Peaceful Path For Kurdish Rights

English

Gazeta Express

12/05/2025 20:14The Kurdistan Workers Party, or PKK, has announced it is dissolving its organizational structure and ending its decades-long armed struggle against Turkey, marking a historic shift after more than 40 years of conflict that has led to the deaths of tens of thousands of people.

The decision, announced on May 12, marks a significant step toward ending one of the region’s longest and deadliest insurgencies, with the group now calling for the Kurdish issue to be resolved through democratic means.

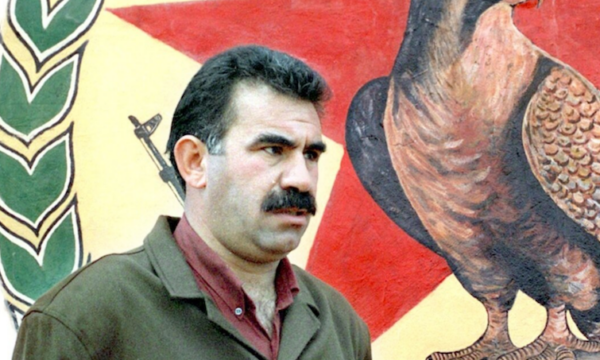

The decision was made during the group’s 12th congress, held last week in northern Iraq, and comes in response to a call from its imprisoned leader, Abdullah Ocalan, who urged the group in February to lay down arms and pursue peace. The announcement was first reported by the Firat News Agency, an affiliate of PKK.

“The 12th PKK Congress has decided to dissolve the PKK’s organizational structure and end its method of armed struggle,” the group said in a statement. “As a result, activities carried out under the name ‘PKK’ were formally terminated.”

Wladimir van Wilgenburg, a political analyst specializing in Kurdish affairs, told RFE/RL that the Kurdish community in Turkey had grown “tired of the conflict and is hoping for peace.”

However, he added that Kurds were not sure whether they could trust the Turkish government and wondered if Ankara would take steps toward reconciliation, such as releasing Kurdish politician Selahattin Demirtas and recognizing Kurdish rights.

“So, they’re a bit mistrustful and unsure about what will happen,” van Wilgenburg said.

Resolution Through Democratic Means

The PKK said the practical process of dissolution and disarmament will be managed and overseen by Ocalan, who has been incarcerated on an island near Istanbul since 1999.

According to the congress declaration, the PKK’s struggle had “brought the Kurdish issue to the point of resolution through democratic politics, thus completing its historical mission.”

The group did not elaborate on what the exactly means, but van Wilgenburg said it was unlikely PKK commanders would enter Turkish politics, seeing as there already is an active pro-Kurdish party in Turkey in the form of Peoples’ Democratic Party (HDP).

“Most likely they mean that from now on Kurdish politics will be conducted through legal politics and the Turkish parliament, not guerrilla warfare,” he added.

The PKK, designated a terrorist organization by Turkey, the United States, and the European Union, began its insurgency in 1984 with the initial aim of creating an independent Kurdish state. In recent years, its demands shifted toward greater autonomy and rights for Kurds within Turkey.

United, But To What Extent?

Earlier this year, the PKK declared a unilateral cease-fire, stating it was “to pave the way for…peace and democratic society,” but set conditions including the creation of a legal framework for peace negotiations.

The group’s statement said its mission had been completed and expressed hope that Kurdish political parties would “fulfill their responsibilities in developing Kurdish democracy and ensure the formation of a Kurdish democratic nation.”

Van Wilgenburg noted that while PKK seems united in its decision, the organization has had issues with splinter groups in the past, such as when Ocalan’s younger brother Osman Ocalan broke away and formed his own short-lived political-military group in 2004.

One key question, van Wilgenburg said, is whether the organization’s affiliates in other countries, such as Iran, will abide by the decision or continue their struggle.

Omer Celik, a spokesman for Turkey’s ruling Justice and Development Party (AKP), demanded on May 12 that the PKK’s decision to disarm and disband be implemented “concretely and in full as well as in a manner comprising all of the PKK’s branches.”

It is estimated that 40,000 people have lost their lives in the PKK-Turkey conflict, with some casualties resulting from PKK attacks on military and civilian targets, as well as Turkish military operations against the group and the communities that supported it.

AdvertisementTë tjera nga rubrika

The Basic Court dismisses the indictment against Klodian Allajbeu, Ekrem Lluka and others

Jessica Simpson Takes Lookalike Daughter to Paris For 13th Birthday Amid Divorce

British couple die after Ferrari plunges off mountain in Spain

Tariffs Temporarily Cut As Talks Narrow Differences

Argentina’s top court finds 80 boxes of Nazi materials in its basement

Why The Tops Of Microwave-Baked Treats Are Ugly And How To Fix Them

AdvertisementTe fundit

“Shumë e trishtueshme”- Trump flet për Princin Andrew pas përfshirjes në Dosjen Epstein: Më vjen keq për familjen mbretërore

“Agjërim sa më të lehtë”, banorët urojnë muajin e shenjtë të Ramazanit

“Kam qenë duke vdekur”, Benita tregon eksperiencën e keqe gjatë një operimi

Londrimi: Unë nuk e kam dërguar Elijonën në finale, e ka merituar

“Diktatorë e tiranë në Bordin e Paqes”, The Guardian s’i kursen as Osmanin e Ramën: Vende pjesërisht të lira e me korrupsion

Ramadani: Drita nuk dorëzohet, besojmë në kualifikim

Advertisement✕